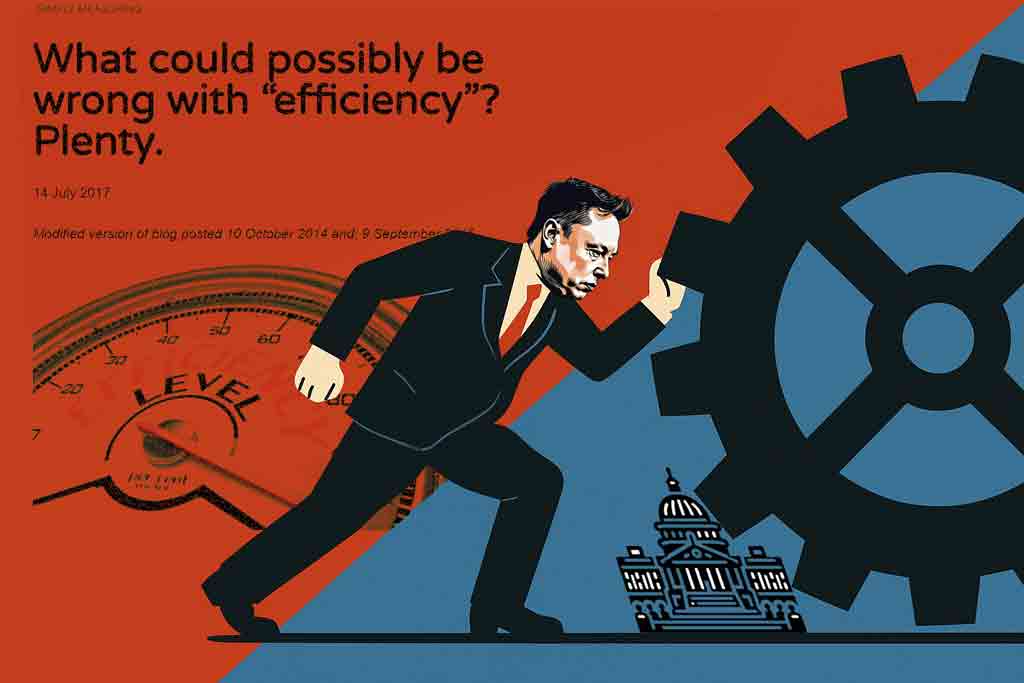

Musk is doing a number on efficiency

2 April 2025

Illustration: Chat GPT and S. Brovkin.

This is a modified version of a blog posted years ago, in anticipation of the American government being torn apart by efficiency.

Efficiency is like motherhood. It gives us the greatest bang for the buck. We decide what benefits we want; efficiency gets us them at the least possible cost. Who could possibly argue with that?

Me, for one, masses of American civil servants, for others.

I list below a couple of things that are efficient. Ask yourself what I am referring to—the first word that pops into your head.

A restaurant is efficient.

Did you think about speed of service? Most people do. Few think about the quality of the food. Is this the way you usually chose your restaurants?

My house is efficient.

Energy consumption always comes out way ahead. Tell me: who ever bought a house for its energy consumption, compared with, say, its design, or its location?

What’s going on here? It’s obvious as soon as we realize it. When we hear the word efficiency, we zero in―subconsciously―on the most measurable criterion, like speed of service or consumption of energy. Efficiency means measurable efficiency: it favors what can best be measured. And herein lies the problem, in three respects:

1. Because costs are usually easier to measure than benefits, efficiency often reduces to economy: cutting measurable costs at the expense of less measurable benefits. Think of all those governments that have cut the costs of health care or education while the quality of those services deteriorated. (I defy anyone to come up with an adequate measure of what a child really learns in a classroom.) How about this student who found all sorts of ways to make an orchestra more efficient? Or those corporate CEOs who cut the quality control budgets or whatever—does Boeing come to mind?—so that they could earn bigger bonuses right away. That’s efficient! (for them).

2. Because economic costs are typically easier to measure than social costs, efficiency can result in an escalation of social costs. Making a factory or a school or diplomacy more efficient is easy, so long as you don’t care about the air or the minds or the treaties polluted.

3. Because economic benefits are typically easier to measure than social benefits, efficiency drives us toward an economic mindset that can result in social degradation. In a nutshell, we are efficient when we eat fast food instead of good food, or don’t answer the phone at Veterans Administration.

So beware of efficiency, and of efficiency experts—efficiency kids too—as well as of efficient education, heath care, and music, sometimes even efficient factories, let alone efficient government departments, where so much that counts can’t be counted. (Efficient tariffs? An efficient White House?) Be careful too of balanced scorecards, because, while the inclusion of all kinds of factors may be well intentioned, the dice are loaded in favor of those that can most easily be measured.

By the way, TwiXer used to be efficient: maximum of 140 characters. (Count them now.) But don’t try to count the trillions from the big boss—not an efficient use of your time.

================

This blog derives from my article “A Note on the Dirty Word Efficiency”, Interfaces (October, 1982: 101-105)

Follow me on LinkedIn, BlueSky, YouTube, and what's left of Twitter, or receive the blogs directly in your inbox by subscribing here. To help disseminate these blogs, we also have a Facebook page.