“Marketing Myopia” Myopia

15 August 2018

Years ago, Theodore Levitt, a marketing professor at the Harvard Business School, published a popular article entitled "Marketing Myopia." Many people in business today, despite not having read the article, subscribe to the idea. It is that companies should define themselves in terms of broad industry perspective rather than narrow product position. To take Levitt's favorite examples, railroad companies were to see themselves in the transportation business, oil companies in the energy business.

The idea was a good one—like all good ideas, within reason. Why not open up perspectives, beyond existing positions: fast food beyond hamburgers (McDonald’s), delivering packages beyond selling books (Amazon), offering unassembled kitchens beyond unassembled tables (IKEA). Just so long as the competencies of the company are respected.

Many firms had a field day with Levitt’s idea, rushing to redefine themselves in all kinds of fancy ways—for example, the mission of a ball bearing company became "reducing friction." It was even better for the business schools. What better way to stimulate the students than to get them musing about how the chicken factory could be in the business of providing protein, or garbage collection could become beautification? Unfortunately, it was all too easy, a cerebral exercise that, while opening vistas, could detach people from the mundane work of plucking and compacting.

Often the problem came down to extravagant assumptions about the intrinsic capabilities of a company—namely that these are almost limitless, or at least highly adaptable. A prominent writer on strategic planning suggested, in apparent seriousness, that "buggy whip manufacturers might still be around if they had said their business was not making buggy whips but self-starters for carriages".1 But what in the world would have enabled them to do that? These two products shared nothing in common—no material supply, no technology, no production process, no distribution channel—save a thought in somebody's head about making vehicles move. Why should starters have been any more of a logical product diversification for them than, say, fan belts? "Instead of being in transportation accessories or guidance systems," why could the buggy whip manufacturers not have defined their business as "flagellation"?2

How can a few clever words on a piece of paper enable a railroad to fly airplanes? Levitt wrote that "once it genuinely thinks of its business as taking care of people's transportation needs, nothing can stop it from creating its own extravagantly profitable growth"3 Nothing except the limitations of its own distinctive competences.

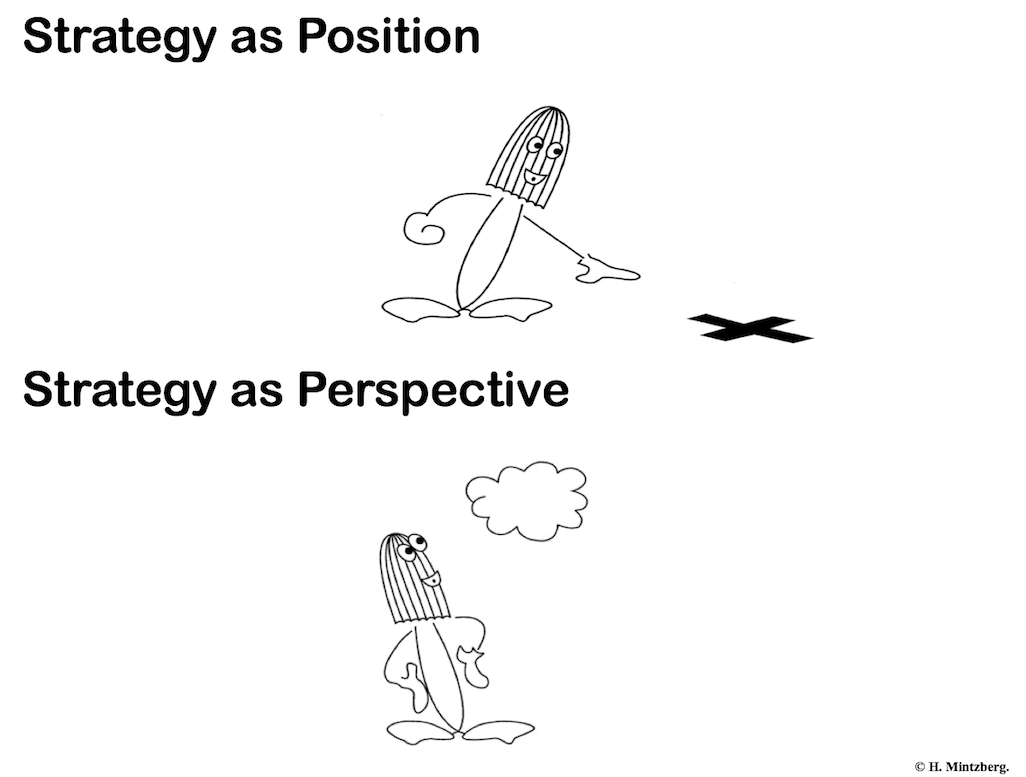

Levitt's intention was to broaden the vision of managers. At that he may have succeeded—all too well. By elevating strategy from past position, to new perspective—from place on the ground to that in some stratosphere—he may have reduced its depth. Market opportunities got elevated past internal strengths. Products ceased to count (railroad executives defined their industry "wrong" because "they were product-oriented instead of consumer-oriented"), as did production ("the particular form of manufacturing, processing, or what-have-you cannot be considered as a vital aspect of the industry"). But what makes marketing intrinsically more important than product or production, or, for that matter, Ludvig in the laboratory? Companies have to build on whatever capabilities they can make use of, without being overwhelmed by weaknesses that they never considered, marketing ones included.

Critics of Levitt's article have had their own field day with the terminology, pointing out the dangers of "marketing hyperopia," where "vision is better for distant than for near objects"4, or of "marketing macropia," which escalates previously narrow market segments "beyond experience or prudence".5 I prefer to conclude that “marketing myopia” has often turned out to be myopic.

© Henry Mintzberg 2018. An earlier version of this appeared in my book The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning, which Tom Peters called “my favorite management book of the last 25 years…no contest.”

Follow this TWOG on Twitter @mintzberg141, or receive the blogs directly in your inbox by subscribing here. To help disseminate these blogs, we also have a Facebook page and a LinkedIn page.

_______________

1 G.A. Steiner, Strategic Planning; What Every Manager Must Know (New York: Free Press, 1979).

2 Heller, quoted R. Norman (1977) Management for Growth, New York: Wiley (p. 34)

3 T. Levitt ,“Marketing Myopia.” Harvard Business Review (July/August 1960, p. 53)

4 P. Kotler and R. Singh, “Marketing Warfare in the 1980s.” Journal of Business Strategy (Winter, 1981:30-41).

5 J.P. Baughman, Problems and Performance of the Role of the Chief Executive in the General Electric Company, 1882-1974 (working paper Graduate School of Business Administration Harvard University, 1974).