Avec des ajouts les 10 et 15 juin 2020

RÉSUMÉ

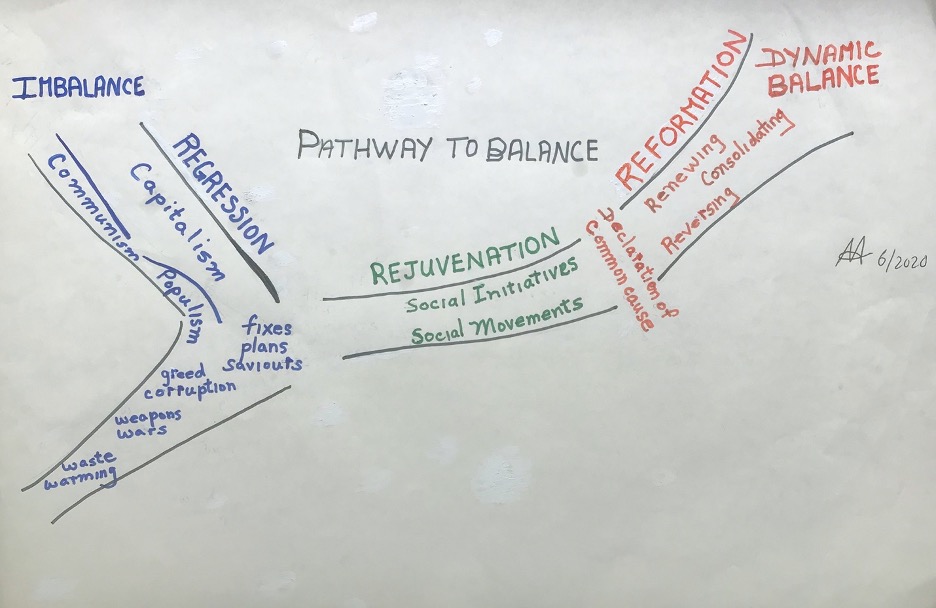

Nous parlons de « nouvelle normalité » tandis que nous retournons à notre ancienne normalité. Cela pourrait nous tuer, plutôt que de tuer notre économie. L’optimisme n’est pas une stratégie. Prendre les devants peut commencer par reconnaître que l’explication dominante de la transmission du coronavirus (le premier niveau – la transmission de proximité) laisse beaucoup à désirer. Comparativement, il y a de plus en plus de preuves d’une autre forme de transmission (le deuxième niveau – la transmission atmosphérique), qui pourrait être responsable de la « superpropagation », tant à l’intérieur qu’à l’extérieur. Le cas échéant, en mettant fin à la pollution, nous pourrions être en mesure de mettre fin à la pandémie. Nous pourrions ouvrir notre économie de façon sélective, en optant pour les activités et les bâtiments qui sont en grande partie non polluants. À court comme à long terme, c’est notre santé qui est en jeu, de même que la santé d’une planète qui en a assez de notre réchauffement.

Nous parlons de « nouvelle normalité » tandis que nous retournons à notre ancienne normalité. Cela pourrait mener à une impasse mortelle. De deux choses l’une, soit nous tuons notre économie en gardant tout fermé ou, dans l’éventualité d’une deuxième vague, nous tuons un plus grand nombre d’entre nous en ouvrant notre économie. L’optimisme n’est pas une stratégie.

Il y a moyen d’aller de l’avant, pour notre santé et celle de notre planète. Après avoir fait du surplace en tentant de publier ce billet dans de nombreux grands journaux (peut-être s’est-il retrouvé aux ordures avec Trump et son eau de Javel), tout en étant convaincu que cela doit être entendu je l’ai publié ici, plus directement, plus nettement, plus clairement1, sous une licence Creative Common afin que vous puissiez le reproduire, le republier, le traduire, voire fixer son résumé à la porte de votre église, votre mosquée, votre synagogue ou votre épicerie préférée.

L’explication dominante de la transmission du coronavirus – par exposition directe à des personnes infectées – laisse beaucoup à désirer. Pourquoi tant de personnes sont-elles infectées sans preuve d’exposition directe? Pourquoi des cas individuels de COVID-19 se dénombrent-ils partout alors que les grandes éclosions sont limitées à des régions et des installations particulières? Qu’est-ce qui a vraiment mis fin aux éclosions à Wuhan et en Corée du Sud? Il doit y avoir une autre explication.

Il y a de plus en plus de preuves de la présence d’une autre forme de transmission, par la pollution atmosphérique. Cette notion a d’abord été rapportée en mars par une équipe de recherche italienne, a été reprise par le journal The Guardian à la fin avril, et a récemment été utilisée avec preuves supplémentaires à l’appui dans un rapport d’un groupe multipartite du parlement britannique2. L’équipe italienne a relevé un lien entre la pollution atmosphérique et la propagation rapide du virus, précisément le fait que des particules minuscules du virus se fixent à des particules d’air pollué. À en juger par des essais antérieurs sur le Zika, le SRAS et l’Ebola, le virus pourrait demeurer actif dans l’air sur plusieurs centaines de mètres, et ainsi infecter des personnes au-delà de quelques mètres.

Cela pourrait expliquer pourquoi, au début du mois d’avril, les dix plus importantes éclosions de la pandémie – en Chine, aux États-Unis, en Italie, en Espagne et en Allemagne – sont survenues dans des endroits où la pollution est importante. La preuve établissant que l’air de plusieurs bateaux de croisière et résidences pour personnes âgées avait des niveaux de contamination élevés suggère que le virus pourrait circuler à l’intérieur par les systèmes de ventilation (comme c’était le cas pour la maladie des légionnaires) ou simplement par la circulation naturelle de l’air à l’intérieur. Comment expliquer autrement que tant de personnes isolées dans leur chambre ont été infectées? Dans son édition du mois de juin, Environment International a invité les « autorités nationales à reconnaître la réalité que le virus se propage par l’air ».

Nous appelons ce deuxième niveau la transmission atmosphérique, par opposition au premier niveau de transmission de proximité.

Le deuxième niveau de transmission atmosphérique est probablement responsable de la « superpropagation », tant à l’intérieur qu’à l’extérieur. Alors que le contact de premier niveau vient expliquer comment des personnes ont été infectées en premier lieu, l’exposition de deuxième niveau pourrait mieux expliquer comment les grandes propagations surviennent, et pourquoi elles se produisent dans certains endroits plutôt qu’ailleurs. Une personne peut transporter le virus d’un endroit à l’autre et infecter les personnes à proximité, mais à partir de là, la pollution atmosphérique pourrait prendre la relève et être responsable de la « superpropagation » puisqu’elle transporte le virus dans l’atmosphère de certaines villes et de certains bâtiments (selon différents facteurs comme l’humidité, l’exposition au soleil et les mouvements de l’air).

Imaginez le deuxième niveau du point de vue de la densité et de la durée des particules actives. La densité de ces minuscules particules dans l’air atmosphérique peut être moindre que celle des particules plus lourdes expectorées dans une pièce. Toutefois, elles peuvent durer plus longtemps, apparemment jusqu’à des heures plutôt que quelques minutes, et être remplacées de façon continue. Nous savons de l’expérience des travailleurs de la santé que plus les gens sont exposés au virus, plus les risques d’infection sont grands. Songez à toutes ces personnes qui sont exposées à la pollution atmosphérique, certaines jusqu’à 24 heures par jour (à l’intérieur comme à l’extérieur). Assistez à un mariage à New York et les chances de rentrer à la maison avec le virus peuvent être plutôt élevées. À quelle fréquence assistez-vous à des mariages? Respirez quotidiennement l’air new-yorkais et le risque d’infection est de 1 %, ce qui correspond à 80 000 personnes. La ville compte 200 000 cas de COVID-19. Est-ce seulement de premier niveau?

Cette preuve devrait nous permettre de reconsidérer notre façon de composer avec la pandémie, ainsi que la façon dont nous l’étudions.

Il nous faut faire un travail de détective, sous la forme d’un apprentissage empirique, en complément de procédures plus formelles de recherche proprement dite. J’ai donné à lire à certains épidémiologistes une version précédente de ce billet. La plupart l’ont rejetée du revers de la main; tous ont indiqué qu’il fallait une recherche plus approfondie; l’un d’eux a dit qu’il faudrait y mettre deux à trois ans. Nous n’avons pas plus le temps d’attendre de tels résultats que nous avons le temps de continuer à aplanir la courbe en attendant un vaccin. Comparez la preuve présentée ici au ramassis de solutions de réouverture actuellement avancées. Quelle preuve vient appuyer la reprise de l’activité dans nos villes polluantes? Bien que la recherche proprement dite doive être faite, il nous faut jouer au détective, c’est-à-dire qu’il nous faut examiner toutes les avenues possibles. Le pari est-il risqué? C’est plutôt la trajectoire actuelle qui est risquée.

Les enjeux sont considérables, alors que les options se font rares. En cessant de croire uniquement en la transmission de premier niveau, toutes sortes d’autres avenues pourraient s’ouvrir à nous. Devrions-nous ouvrir les fenêtres pour aérer l’intérieur des bâtiments? Pas si l’air extérieur apporte davantage de dangers. Devrions-nous retirer nos masques s’il n’y a personne à proximité (comme c’est présentement le cas dans certains hôpitaux) ou permettre aux écoles et aux usines de rouvrir tant que tout le monde respecte la distanciation? Pas si on découvre que l’air intérieur contient des contaminants qui pourraient faire circuler le virus.

En mettant fin à la pollution, tant à l’intérieur qu’à l’extérieur, nous pourrions mettre fin à la pandémie. La Chine et la Corée du Sud ont été saluées pour avoir confiné leur population afin d’aplanir la courbe. Toutefois, un avantage important est fortuit. Avec moins de circulation automobile et d’activité industrielle, l’éclosion pourrait avoir pris fin parce que la pollution a diminué. Le cas échéant, le simple fait de rouvrir notre économie, bien que graduellement, pourrait s’avérer mortel. C’est ce que nous verrons peut-être avec la venue d’une deuxième vague.

Allons-nous nous retrouver dans une voie sans issue, d’une manière ou d’une autre, entre des options biaisées de réouverture ou de fermeture? Nous pouvons rouvrir notre économie de façon sélective, là où la distanciation est possible, en permettant aux activités peu polluantes de reprendre leur cours tout en freinant l’ouverture des grandes sources de pollution – certaines centrales électriques et usines ainsi que la plupart de la circulation automobile – jusqu’à ce qu’elles puissent être assainies, si c’est possible. À l’intérieur, nous pouvons examiner tous les endroits problématiques, les résidences et les écoles, les bureaux et les arénas, les usines et les usines de transformation du porc, et ne permettre leur réouverture qu’une fois que les experts confirmeront que l’air ambiant ne fait pas circuler le virus. (Dans ces usines, comme dans les marchés chinois et les sites funéraires indiens3, la fumée est peut-être un facteur.)

Fondamentalement, il faudra peut-être stopper la pollution pour stopper la pandémie (#SP2SP). Qui plus est, il nous faut stopper la pollution de nos corps et de nos esprits pour rééquilibrer nos sociétés (#SP2RS). La solution est peut-être drastique, mais pas autant que ce que nous faisons présentement.

__________________________________________

Dans un sondage mené en 2003, John Snow a été élu par un panel de médecins britanniques comme le meilleur d’entre eux. Au cours de sa vie, toutefois, John Snow a été écarté par le corps médical britannique pour avoir remis en question la conviction admise portant que le choléra devait se transmettre par l’air. Pendant une épidémie à Londres en 1854, il a marqué d’une épingle sur une carte de la ville chaque endroit où il y a eu un décès. À l’exception de deux, ces épingles étaient regroupées autour d’un puits. Il s’est rendu à la maison d’une des deux personnes décédées ailleurs et a appris qu’elle aimait l’eau de ce puits, qu’elle envoyait sa domestique chercher. Sa nièce, qui buvait également l’eau de ce puits, s’avérait être l’autre exception. Ainsi, alors que le corps médical s’efforçait frénétiquement de contrer l’éclosion de choléra, la poignée du puits a été retirée et l’épidémie a pris fin. Ce n’était toutefois pas la fin du choléra. Il aura fallu 12 ans, et bien d’autres décès, avant que la transmission du choléra par l’eau polluée soit finalement reconnue. Combien de temps, et d’autres décès, faudra-t-il avant que la transmission de la COVID-19 par l’air pollué soit même prise en compte? Nous ne disposons pas de 12 semaines.

__________________________________________

Nous avons besoin d’une victoire. Reconnaître le deuxième niveau de transmission en complémentarité du premier niveau présente des avantages : un pas vers l’avant pour notre santé immédiate et à long terme ainsi que pour la santé d’une planète qui en a assez de notre réchauffement. Et si nous prenions l’idée au sérieux, mais qu’elle s’avérait erronée? Tant mieux. Enfin, nous aurons pris soin de notre santé à long terme et nous nous serons occupés du réchauffement climatique. Allez, un peu de sérieux!

© Henry Mintzberg 2020. Ce billet est publié en vertu d’une licence internationale de Creative Commons selon une attribution non commerciale, version 4.0. Pour en savoir plus sur la rectitude en matière de soins de santé, consultez mon ouvrage Managing the Myths of Health Care.

Je suis reconnaissant à tous ceux, dont certains n’adhéraient pas nécessairement à mon point de vue, qui ont contribué à cet effort au cours de ces deux derniers mois un peu fous.

À la recherche : Hanieh Mohammadi, Paola Adinolfi, Simon Hudson, Alex Anderson, Pierre Batteau et Diane Marie Plante

À la suggestion de sources : Natalie Duchesne, Lisa Mintzberg, Susan Mintzberg, Leslie Breitner, John Breitner, Joanne Liu, Jonathan Gosling, Karl Moore, Rosamund Lewis et Donald Berwick

Au soutien professionnel : Rick Fleet et Jean-Simon Létourneau, avec notre groupe Blindspot [angle mort] de mcgill.ca/imhl, Toby Heaps et Corporate Knights, Matthew Chapman et la Coalition Climat Montréal, ainsi que Bill Litwack pour des révisions antérieures

Au soutien en coulisses : Santa Balanca-Rodrigues, Phil LeNir ainsi que Marie-Michèle Naud

Et finalement, mais surtout, au soutien substantiel autant que personnel : Dulcie Naimer

Suivez ce TWOG sur Twitter @mintzberg141, ou recevez les blogues directement dans votre boîte de réception en vous abonnant ici. Pour aider à diffuser ces blogues, nous avons également des pages Facebook et LinkedIn.

1 Mon blogue du 31 mars, Enquête sur la cause du coronavirus, relevait ce que je considère être certaines anomalies liées au coronavirus. Le 2 avril, j’ai reçu un courriel de Nathalie Duchesne au sujet du rapport de l’équipe de recherche italienne, auquel j’ai rapidement répondu : « C’est incroyable! Le virus circule peut-être dans l’air! Je réfléchissais justement aux particules. Ainsi, retirer les voitures des routes pourrait mettre fin à tout ceci! » J’ai ensuite publié Deuxième partie : Expliquer les anomalies, le 5 avril. Depuis lors, j’ai réécrit ce billet plus d’une vingtaine de fois (avec une révision publiée ici le 2 mai), tout en tentant de le faire publier comme lettre d’opinion dans de nombreux grands journaux. Deux ont refusé, alors que cinq autres n’ont pas répondu. (Trop peu de science pour une lettre d’« opinion »). Éventuellement, j’aimerais rédiger un blogue sur le scientisme en temps de COVID-19.

2 Le 29 mai, dans une prépublication de medRxiv, une équipe de recherche de l’unité de toxicologie du CRM de l’Université de Cambridge a rapporté que « [son] modèle indiquait que l’exposition à PM2,5 et PM10 [polluants présents dans l’air extérieur et intérieur] augmentait le risque d’infection à la COVID-19 ».

3 Des usines d’emballage de viandes ont été des foyers d’éclosions importants de COVID-19, apparemment davantage que d’autres usines où les gens travaillent également très proches les uns des autres. Le 24 avril, la BBC a rapporté que « lorsque des scientifiques ont analysé les dossiers des admissions dans les hôpitaux du Brésil, ils ont découvert que le taux de cas de grippe tendait à augmenter durant la saison sèche, alors qu’il y a plus de fumée dans l’atmosphère… » Le rapport expliquait que la fumée bloquait les rayons ultraviolets du soleil qui auraient tué le virus. Cependant, comment ce virus circule-t-il dans l’atmosphère en premier lieu? Si le coronavirus se fixe également aux particules de fumée, est-ce que cela pourrait venir expliquer certaines de ces éclosions : que l’air infecté par le processus de fumage des viandes comme le bacon et le jambon pourrait être responsable de la « superpropagation », dans ces usines et/ou dans les communautés environnantes? « Un petit nombre d’employés des usines du Wisconsin et du Missouri ont obtenu un résultat positif au test de dépistage de la COVID-19… Ces deux usines sont situées à proximité d’endroits où “la propagation communautaire de la COVID-19 est importante” » (Business News). D’ailleurs, la fumée du grillage de viandes dans les marchés chinois apporterait-elle peut-être une meilleure explication de la propagation du coronavirus que la présence d’animaux exotiques? Et qu’en est-il des bûchers funéraires en Inde? Plus les gens meurent, plus il y a de cas de COVID-19.