Need a strategy? Let it grow like a weed in the garden

23 October 2016

Hothouse Dick sitting among the weeds, photo by HM

Searching for a strategy? Here’s how to get one, according to just about every book and article on the subject. I have stylized this a bit, in what I call the Hothouse Model of Strategy Formulation.

1. There is one prime strategist, and that person is the chief executive officer. Other managers may participate, and planners provide support, while consultants offer advice (sometimes they even offer the strategy itself—but don’t tell anybody).

2. The chief analyzes the appropriate data and then formulates the strategy through a controlled process of conscious thought, much as tomatoes are cultivated in a hothouse.

3. The strategy comes out of this process immaculately conceived, then to be made formally explicit, much as ripe tomatoes are picked and sent to market.

4. This explicit strategy is then systematically implemented, which includes the development of necessary budgets as well as the design of appropriate structure. (If the strategy fails, blame “implementation”, namely those dumbbells who were not smart enough to implement your brilliant strategy. But be careful, because if the dumbbells are smart, they will the ask “Why, if you are so smart, did you not formulate a strategy that we dumbbells were capable of implementing?” You see, every failure of implementation is one of formulation.)

5. Hence to manage this process is to plant your strategy carefully and watch over it as it grows on schedule, so that the market can beat a path to your products and services.1

Wait, don’t go off and start your strategy quite yet. First read what I call a grassroots model of strategy formation.

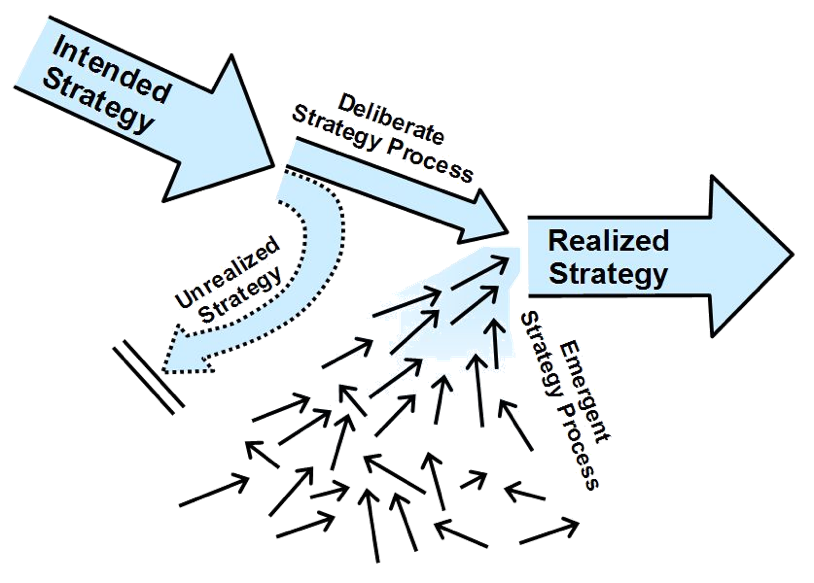

1. Strategies grow initially like weeds in a garden; they are not cultivated like tomatoes in a hothouse. In other words, the process of creating strategies can be over-managed. Sometimes it is more important to let ideas emerge than to force a premature consistency on the organization. Allow those strategies to form, as patterns, not having to be formulated, as plans. The hothouse, if needed, can come later.

2. These strategies can take root in all kinds of strange places, virtually wherever people have the capacity to learn and the resources to support that capacity. Sometimes an individual in touch with an opportunity can create his or her own idea that evolves into a strategy. An engineer meets a customer and gets an idea for a new product. No discussion, no planning: she just builds it and sells it. The point is that organizations cannot always plan where their strategies will emerge, let alone plan the strategies themselves.

3. Ideas become strategies when they pervade the organization. Other engineers see what she has done and follow suit. Then the salespeople get the idea. Next thing you know, the organization has a new strategy—a new pattern in its activities—which might even come as a surprise to the central management. After all, weeds can proliferate and encompass a whole garden; then the conventional plants look out of place. Likewise, newly emerging strategies can sometimes displace existing deliberate ones. But, of course, what’s a weed but a plant that wasn’t expected? With a change of perspective, the emerging strategy can become what’s valued, much as Europeans enjoy salads of the leaves of dandelions, America’s most notorious weed.

4. The processes of proliferation may or may not be consciously managed. As noted above, the pattern can just spread by collective action, much as plants proliferate themselves. Of course, once strategies are recognized as valuable, the processes by which they proliferate can be managed, just as plants can be selectively propagated. Then it may be time to build that hothouse—make that emergent strategy deliberate going forward.

5. There is a time to sow strategies and a time to reap them. The blurring of the separation between these two can have the same effect on an organization that the blurring of the separation between sowing and reaping can have on a garden. Managers have to appreciate when to exploit an established crop of strategies and when to encourage new strains to replace them.

6. Hence to manage this process is not to preconceive strategies but to recognize their emergence and intervene when appropriate. A destructive weed, once noticed, is best uprooted immediately. But one that seems capable of bearing fruit is worth watching, indeed sometimes worth building a hothouse around. Managing in this context means ensuring a flexible structure that encourages the generation of a wide variety of ideas and establishing a climate within which such ideas can grow, then to notice what does in fact come up, and support the best of it. But you must not be too quick to cut off the unexpected: sometimes it is better to pretend not to notice a newly emerging strategy until it bears some fruit, or else withers.

OK, now you are all set to go out and create strategies: by forgetting the word, getting involved in the details, and doing a lot more learning than planning.

© Henry Mintzberg 2016. This TWOG is adopted from pages 214-216 of my book Mintzberg on Management, which is the best collection of my earlier writings.

1Aside from the work of Michael Porter, see Dick Rumelt’s book Good Strategy/Bad Strategy. Neither author would, of course, quite subscribe to this characterization of their work, but both offer the best of this approach.

Follow this TWOG on Twitter @mintzberg141, or receive the blogs directly in your inbox by subscribing here. To help disseminate these blogs, we also have a Facebook page and a LinkedIn page.