Time for Management Education

19 December 2014There is plenty of business education, but hardly any management education. In the last three TWOGs, I have been critical of this business education, because of the harm I believe it has been doing to the practice of managing. In this TWOG, I describe a very different form of education, to focus away from heroic leadership, toward engaging management.

For years I was going around giving talks about these concerns. Eventually people starting asking me: “What are you doing about it?” I’m a professor: we are supposed to criticize, not do anything about anything. But duly embarrassed, with colleagues from McGill in Canada and at business schools in England, India, Japan, and France (later China and Brazil), we created the International Masters in Practicing Management (impm.org). This is an emba all right—experiencing management by action.

While a manager cannot be created in a classroom, people who practice management can benefit enormously by reflecting on their own experience and sharing the insights with each other. This kind of social learning has proved to be the most powerful pedagogical tool we have. T.S. Eliot wrote in one of his poems that “We had the experience but missed the meaning.” We all have to get the meaning of our experiences. Saul Alinsky suggested further, in his book Rules for Radical, that we do not accumulate experience; we undergo “happenings.” These “become experiences when they are digested [and] reflected on…”

Accordingly, the managers who participate in our program (average age early 40s) stay on the job—this is about doing a better job, not getting a better job—and come into the classroom periodically for 10-day modules—five in all over a 16 months. These focus, not on the functions of business (marketing, finance, etc.), but on the mindsets of managing: reflection (managing self), analysis (managing organizations), worldliness1 (managing context), collaboration (managing relationships), and action (managing change).2 At the end of our very first module, on reflection, while everyone else was going around saying “It was great meeting you!” Alan Whelan, a sales manager at BT, was saying: “It was great meeting myself!”

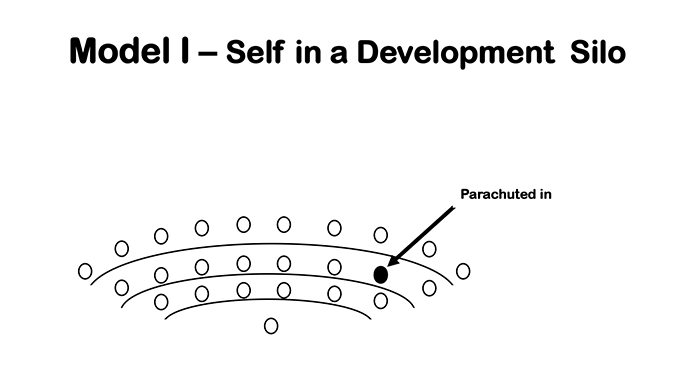

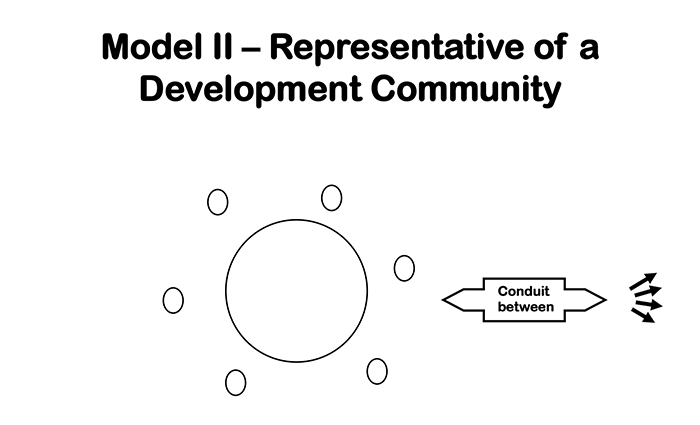

We have a 50:50 rule in the classroom: half the time over to the managers on their agendas. Thus they sit at round tables in a flat room, so they can go in and out of workshops at a moment’s notice. No need to “break out.” These managers are not lone wolves, parachuted into the class to sit in silos, but people engaged in their development, linked back to their workplaces (see Models 1 and 2).3 This has opened the door to a variety of novel practices.

“This is the best management book I ever read” Silke Lehnhardt told her colleagues back at Lufthansa. Every day in the program, starting with morning reflections, everyone records their thoughts in the empty Insight Book we give them—anything and everything about being a manager, on the job, in the business, and about life. They share these thoughts with colleagues around the table and then the best insights are discussed altogether in a big circle. Shouldn’t every manager’s best book be the one they have written for themselves?

We all have our own concerns. It is quite remarkable what can happen in friendly consulting, where a concern of each manager becomes the focus of attention of a small group of experienced colleagues dedicated to helping him or her think it through. One manager’s boss quit suddenly during the program and she was struggling with whether to take that position and give up what she had been developing in her own job. The hour of friendly consulting was so helpful that they carried on over lunch. (More on the process in a later TWOG.)

Mayur Vova was running his jam and jelly company in Pune, India, while Françoise LeGoff was number two on the Africa desk at the Red Cross Federation in Geneva. We were going to introduce managerial exchanges, a new element in the program, at an upcoming module. The managers were to pair up and spend a week at each others’ workplaces. But these two got a head start, before we could even brief them about it. When they arrived at the module, the two of them accosted me: they couldn’t wait to tell me about the experience. At the start of that week, Mayur saw Françoise typing and asked: “Can’t a secretary do that?” Welcome to the worldly mindset: Geneva is not Pune. On the last day, Mayur proposed to Françoise that he would be happy to meet with any of her staff. All of them lined up to convey through him their impressions of her management style. Better than a 360! Mayur “was like a mirror for me,” Françoise reported.

We encourage each manager to form an IMPact Team back at work, to carry the learning of the program back into his or her company for reflection and action. One small company ran into a serious problem, and the manager in the program found himself picking up the pieces. He and his colleagues formed such a team to focus their discussions: he believed it saved the company.

The IMPM has been spreading internally. For example, Renmin University in Beijing, which runs the module on collaboration, has created a CMPM for China. And at McGill we have developed the International Masters for Health Leadership (mcgill.ca/imhl), for experienced people from all aspects of health care. But the pedagogy has been slow to spread to other business schools although I have written extensively on it.4 Maybe they are too busy teaching cases about how the established companies missed the new technology.

Is this the new technology? You have to see it to believe it.5

The MBA is fine so long as it is recognized for what it does well, namely train people for certain specialized jobs in business, but also for what it does badly, namely prepare people for managing. Beyond the MBA, it’s time for management education.

1. Not global: this is not about becoming cookie cutter global, but getting into other people’s worlds in order to better understand one’s own (more on this in a later TWOG).

2. Gosling, J. & H. Mintzberg. (November 2003). The Five Minds of a Manager, Harvard Business Review.

3. In contrast, Wharton, one of the most prominent business schools, has for years been telling people on its website that, in the current wording (accessed this week): “Our executive MBA program is a full-time-equivalent MBA program offered in an executive format. Students in the full-time and executive programs “[f]ollow the same curriculum…” Imagine claiming that they do the same for people with much experience as for those with little. http://executivemba.wharton.upenn.edu/program-details/compare-wharton-pr...

4. Looking Forward to Development Training & Development (13 February 2011); From Management Development to Organization Development with Impact OD Practitioner (2011,Vol. 43 No. 3); Developing Naturally: from management to organization to society to selves, in Snook, Nohria, and Khurana (eds.) The Handbook for Teaching Leadership. Sage (2012); Managers not MBAs Berrett-Koehler (2004).

5. Phil LeNir saw it, and took it in a different direction, out of the university. He was an engineering manager at a high tech company, concerned about developing his young managers, but with no budget for this or help from HR. He asked me what to do and I suggested that he get them around a table periodically for reflections and the sharing of experience. Over the course of two years, that worked so well—some of his managers started to do the same thing with their people—that we set up CoachingOurselves.com as a kind of do-it-yourself management development program. Now groups of managers in their own workplaces are downloading topics and engaging in social learning to address their common concerns. The IMPact group mentioned above made extensive use of CoachingOurselves in turning around its company.

© 2015 Henry Mintzberg